These visionary African American activists were some of the most vocal agents for racial change.

By Brad Witter Updated: Jan 11, 2021 5:08 PM EST

The 1865 ratification of the 13th Amendment legally ended slavery in the United States, but, for the victims of the Atlantic slave trade, it also marked the beginning of a new era of oppression. Violence and racism — both blatant and institutional — ran rampant, especially in the South, where the discriminatory Jim Crow Laws laid the groundwork for racial segregation following the post-Civil War Reconstruction Era.

By the 1950s, after enduring nearly a century of inequality, segregation, as well as vicious lynchings and other senseless acts of violence, a group of African American activists began the civil rights movement. Over the course of the next two decades, countless Black men and women mobilized, organizing boycotts, sit-ins, and nonviolent protests such as the 1961 Freedom Rides and the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in an effort to fight back against systematic oppression.

Thanks to their tireless efforts — often in the face of jail time, beatings, and, in some cases, death — Congress eventually passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ending segregation in public places and banning employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. One year later, U.S. lawmakers also passed another landmark piece of civil rights legislation: the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

None of this progress could have been made without the work of several visionary Black activists. Here are some of the civil rights movement's most vocal agents of change:

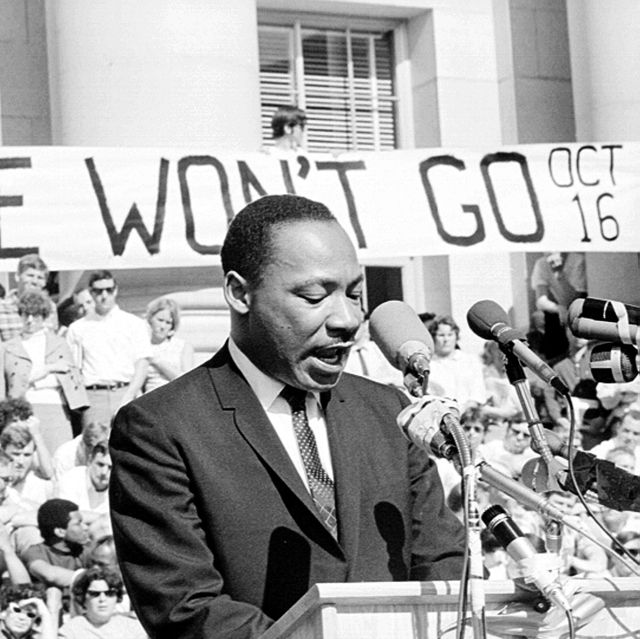

Martin Luther King Jr. delivers a speech to a crowd of approximately 7,000 people on May 17, 1967, at UC Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza in Berkeley, California.

Widely recognized as the most prominent figure of the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. was instrumental in executing nonviolent protests, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech. The following year, the Baptist minister became the youngest person to win the Nobel Peace Prize at just 35 years old.

Throughout his life, the civil rights leader was reportedly imprisoned nearly 30 times for acts of civil disobedience, among other unreasonable charges. (Montgomery, Alabama police once jailed King for driving 30 miles per hour in a 25-mile-per-hour zone.) While behind bars in 1963, King penned his famous Letter From Birmingham Jail, which included the famous quote, "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere."

On April 4, 1968, Missouri State Penitentiary fugitive James Earl Ray assassinated the 39-year-old King, who was standing on the second-floor balcony of Memphis, Tennessee hotel, Lorraine Motel. Following King's murder, his wife and fellow activist Coretta Scott King continued their work towards justice by founding Atlanta's Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change (also known as the King Center).

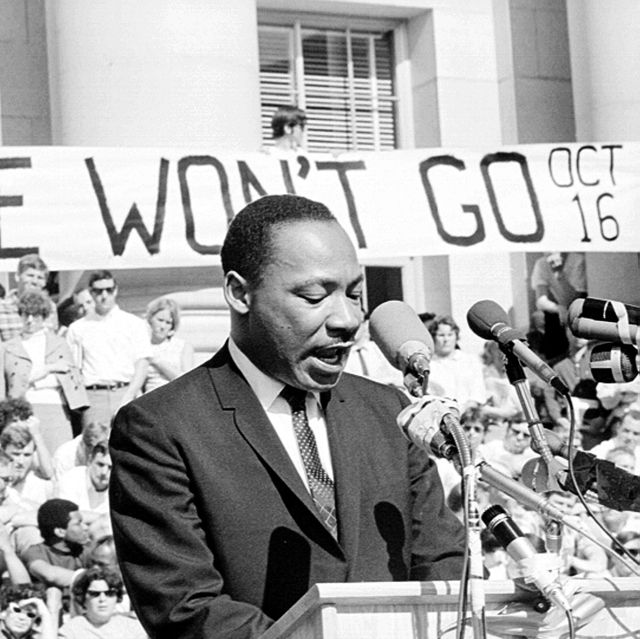

In stark contrast to King's championing of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience, Malcolm X famously preached defending oneself "by any means necessary," thus sparking what many considered to be a radicalized, potentially violent version of the civil rights movement.

While serving a 10-year prison sentence for a larceny conviction, he converted to the Nation of Islam, which promoted Black supremacy and rejected the idea of integration.

Following his 1952 prison release, Malcolm X became a spokesman for the Nation of Islam, and under his leadership, its membership grew from 400 members to 40,000 members by 1960.

Malcolm X eventually left the Nation of Islam in 1964 and later converted to traditional Islam during a pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Upon returning to the United States, he had shifted ideologies and was more optimistic toward a peaceful resolution to the fight for civil rights. On February 21, 1965, Malcolm X was preparing to give a speech for his Organization of Afro-American Unity at New York City's Audubon Ballroom when several members of the Nation of Islam shot and killed him.

Often referred to as "the mother of the civil rights movement," Rosa Parks, a seamstress, put a spotlight on racial injustice when she refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama on December 1, 1955. Her arrest and resulting conviction for violating segregation laws launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which was led by Dr. King and boasted 17,000 Black participants.

The year-long boycott ended in December 1956 following a U.S. Supreme Court decision declaring Montgomery’s segregated seating unconstitutional. During that time, Parks lost her job and, in 1957, relocated to Detroit, where she served on Michigan Congressman John Conyers, Jr.'s staff and remained active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

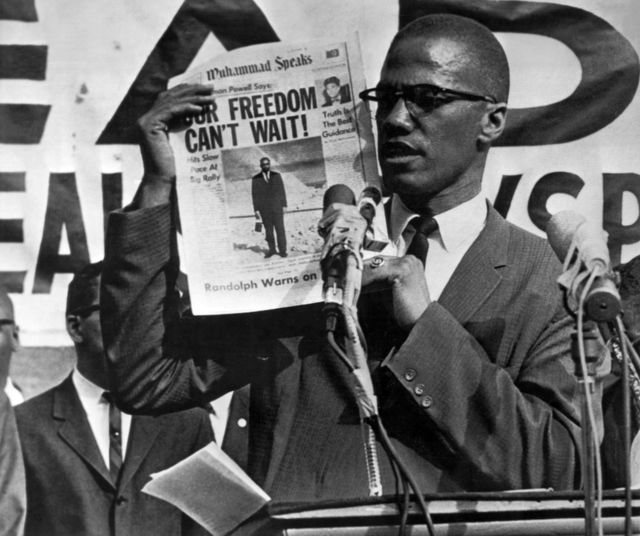

John Lewis, who's served as a Georgia congressman since 1986, learned about nonviolent protest while studying at Nashville's American Baptist Theological Seminary and went on to organize sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. Eventually earning the title of chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Alabama native was beaten and arrested while participating in the 1961 Freedom Rides.

After speaking at the 1963 March on Washington, he led a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on March 7, 1965. During what became known as "Bloody Sunday," state police violently attacked the marchers as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and Lewis suffered a fractured skull. The day's horrific images led President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Bayard Rustin was a close adviser to Dr. King beginning in the mid-1950s who assisted with organizing the Montgomery Bus Boycott and played a key role in orchestrating the 1963 March on Washington. He's also credited with teaching King about Mahatma Gandhi's philosophies of peace and tactics of civil disobedience.

After moving to New York in the 1930s, he was involved in many early civil rights protests, including one against North Carolina's segregated public transit system that resulted in his arrest. (Rustin was eventually sentenced to work on a chain gang.) An openly gay man, Rustin also advocated for LGBT rights and spent 60 days in jail for publicly engaging in homosexual activity.

Aside from heading prominent civil rights era organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), James Farmer also organized the 1961 Freedom Rides, which eventually led to interstate travel desegregation. The Howard University graduate was also a follower of Gandhi's philosophies and applied their principles to his own acts of nonviolent civil resistance.

While trying to organize protests in Plaquemine, Louisiana, in 1963, state troopers armed with guns, cattle prods and tear gas, hunted him door to door, according to CORE's website, which noted that Farmer eventually went to jail on charges of "disturbing the peace."

As far as his further impact on the civil rights movement, New York Times reporter Claude Sitton reportedly wrote: "CORE under Farmer often served as the razor's edge of the movement. It was to CORE that the four Greensboro, N.C., students turned after staging the first in the series of sit-ins that swept the South in 1960. It was CORE that forced the issue of desegregation in interstate transportation with the Freedom Rides of 1961. It was CORE's James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — a Black and two white people — who became the first fatalities of the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964."

After nearly being killed for using a white people-only water fountain in Georgia, Hosea Williams joined Savannah's chapter of the NAACP in 1952. Twelve years later, he joined King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference as an officer, assisting with Black voter registration drives in the Freedom Summer of 1964.

Along with Lewis, he also played a leadership role in the 1965 March to Montgomery that became known as "Bloody Sunday." That same year, King appointed him president of the SCLC's Summer Community Organization and Political Education.

Williams, who witnessed King's 1968 assassination, was elected to the Georgia State Assembly in 1974.

As the executive director of the National Urban League, beginning in 1961, Whitney Young Jr. was responsible for overseeing the integration of corporate workplaces. Throughout his 10 years in the position, he took up the cause of equal opportunities for Black in industry and government service. At his direction, the National Urban League also co-sponsored the 1963 March on Washington.

On the political front, the World War II veteran acted as an adviser on racial matters to President Lyndon B. Johnson, and his Domestic Marshall Plan is said to have heavily influenced 1960s federal poverty programs. Young received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1968.

Roy Wilkins served as assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White in the early 1930s and succeeded W.E.B. Du Bois as the editor of the organization's official magazine, Crisis, in 1934. During Wilkins' tenure, the NAACP played a major role in civil rights victories, including Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

A subscriber to the philosophy that reform is best achieved via legislation, Wilkins testified before Congress multiple times and also consulted for several U.S. presidents. Among the watershed events he participated in: the 1963 March on Washington, 1965's "Bloody Sunday" Selma to Montgomery march and the March Against Fear in 1966.

Martin Luther King, Jr. delivers a speech to a crowd of approximately 7,000 people on May 17, 1967 at UC Berkeley's Sproul Plaza in Berkeley, California

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

James Farmer, the Executive Director of the Congress for Racial Equality, sits next to a uniformed officer in the back of a police wagon

Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

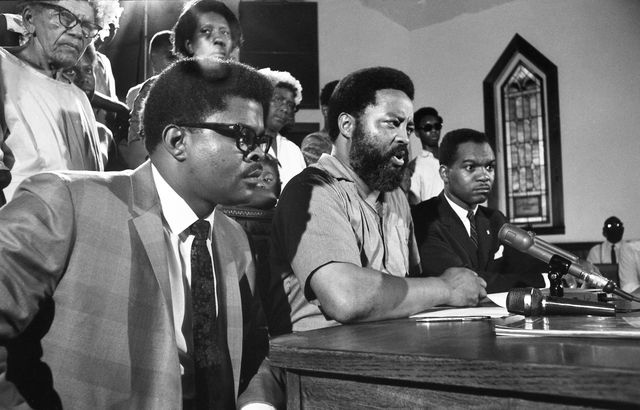

Reverend Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (center) and some of his "poor people," appear at a news conference. Williams, the Reverend W.C. Wales of Cocoa (left), and Walter e. Fauntroy (right) of Washington announced plans for demonstrations to coincide with the launch of Apollo 11. July 14, 1969 (Bettmann Archive/Getty Images)

Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Whitney M. Young, Jr reads a statement condemning the racial violence sweeping the country as unjustified during a news conference

Photo: Getty Images

Roy Wilkins (l), Executive Secretary of the NAACP, and Medgar Evers, (c) NAACP field secretary who are picketing outside of a Woolworth's department store in Jackson, Mississippi.